|

| Appalachian mountain dulcimer |

The Dulcimer

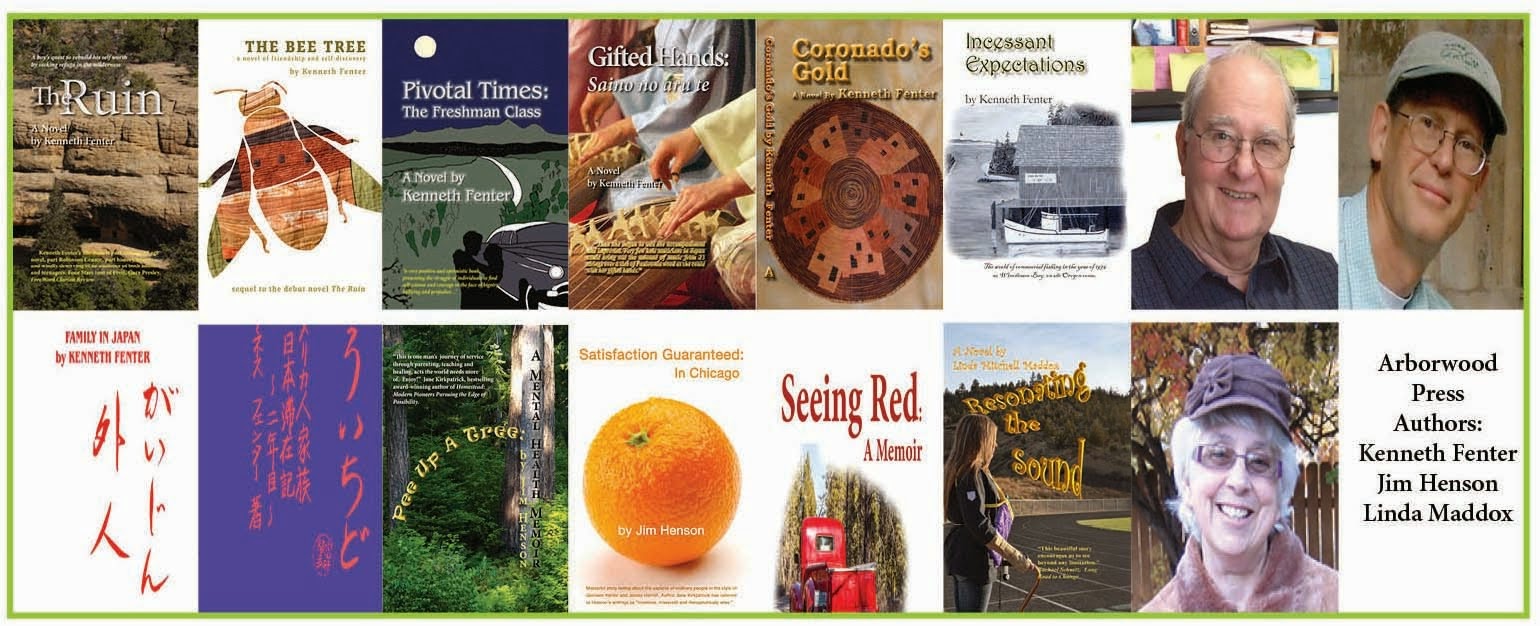

By Kenneth Fenter,

Christmas 2002

Osamu Kitajima sat on the hood of his rental car at one of the

overlooks in the Great Smokey Mountain National Park. To the horizon, the

Appalachians undulated with steep slopes, and narrow canyons completely covered

with brilliant red, yellow, crimson and green. A blue autumn haze hung over the

ridges and flowed down into the valleys causing the “smoky” look of the park’s

namesake. He stared trance-like across the broad country, mentally comparing

the immensity of the park and its character to his home area in Japan. Even

though he had admired the mountains many times before, he never tired of their

timeless beauty. From the car stereo drifted a haunting melody of a bamboo shakuhachi

flute, which pushed him deeper and deeper into his meditation.

Mama raccoon looked out the hole 40 feet above the ground in the

trunk of the ancient walnut tree. Below her, other denizens of the Appalachian

mountainside scratched for food under leaves and rocks in the early evening

twilight. A pileated woodpecker landed higher up on the trunk and began his

“rat a tat tat” search for grubs under the rough bark. A graceful doe stepped

daintily, warily down the narrow game trail at the foot of the tree.

Trees in brilliant fall plumage surrounded the walnut. Giant

rhododendron and azalea mixed with mountain laurel and ferns. Spanish moss hung

from trees. The raccoon eyed a wild persimmon with bright red fruit hanging

among the few remaining leaves. A sweet persimmon would be the fare of choice

on this autumn evening.

Life for the walnut tree continued much as it had for the 250

years that it had stood. During those two and a half centuries, the tree had

witnessed members of several Indian nations trot down the narrow trail on their

way to neighboring villages, on hunts, or to war. Wide-eyed slaves had slipped

up the trail toward a dream of freedom, only to be driven back later in chains.

The tree had felt the vibrations of gunshots as gray suited soldiers had

ambushed cousins wearing blue. Young couples had secretly used its branches to

climb in as they advanced their courtship. Intermittent fires had swept up the

slope and singed its leaves and bark but had not killed it. Years had turned to

decades, decades to centuries and after all that time the tree still stood

proud and straight, its branches spreading wide, providing shelter and food for

the animals and birds. It had escaped the axes that had felled many similar

trees to build forts, barns, houses or fence posts in the early days of

settlement by farmers and woodsmen.

But recently the tree had felt other vibrations that were more

ominous than footsteps or gunshots in the past. Sounds of metal treads and

buzzing chain saws mingled with the sound of the breezes, birds and insects of

the forest.

A half mile away, the timber faller for a right of way crew lifted

a bottle and took a deep draft of cool water. As he drank, he looked ahead into

the mass of old-growth trees. A narrow band of trees bore red ribbons

designating ones to be felled so that the heavy equipment could pass through to

hew out a right of way for a power line. He lowered the bottle and studied the

amazing assortment of hardwoods and cedar that made up the forest. With regret,

he returned the water to his pack and picked up the chain saw.

On another morning, the mother raccoon awakened to a sudden loud

buzzing sound 40 feet below. She crawled to the entrance of her den and looked

down at the tall woodsman who turned his chain saw sidewise and held the

whirring chain to the trunk of the giant walnut. The vibration from the chain

transmitted up the trunk and woke the two cubs who were curled behind her.

“Shhh,” she chattered. “Be still. It will go away. It is the same as we have

heard every day, and every day it has gone away,” she told her anxious cubs.

They huddled close to her and peered out the hole to look at the action below.

There were no other sounds in the woods. The birds had flown. The other small

animals had fled to their dens at the first annoying sound of the chain saw.

Minutes seemed as hours as the man labored at cutting the tree

until finally the giant trunk shuttered in throws of death and began to keel to

one side, slowly at first and then more rapidly until it crashed to earth with

a thunderous roar.

“Are you okay?” The shaken raccoon mother asked as she examined

her half grown babies.

“What will we do?” the smaller one asked, dazed by the impact.

“We will get away from here as fast as we can,” her mother

chattered as she gathered her two cubs by the scruff of their necks and crawled

through the opening to drop to the ground and scurry away to find a new hiding

place.

“Such a magnificent tree,” the woodsman said aloud. He examined

the rings of the freshly cut trunk. “You have been here for a long time, but

you are just as solid as a rock. I promise that you will be put to good use,

old girl. I know a mill that will turn you into pieces of fine art that will be

heirlooms five hundred years from now.” The woodsman refueled his saw and

carefully began cutting the branches from the giant trunk. Many of the branches

were larger than the trunks of the younger trees he had felled that morning.

Late that afternoon the loader crane lifted three large straight

logs of the trunk onto a dusty, rusty, log truck. The branches, some straight,

and some bent and twisted, were loaded onto another truck. Branches that were

too small to be sawn into planks and the top portion of the main trunk were

loaded onto yet another truck.

The first two trucks deposited their stack of prize hardwoods at a

small sawmill near the Craft Setlement

at Nawger Nob, Townsend, Tennessee, where it would be cut into thick slabs of

lumber from which fine furniture builders from all over the world would pay

small fortunes.

The third truck carrying the smaller branches delivered to a

different part of the mill where smaller saws specialized in cutting oak and

miscellaneous bent and twisted hardwood logs into rough narrow boards to be

made into pallets. The pallets would be shipped to local factories onto which

products would be fastened so that forklift trucks could move the merchandise

to trucks, trains and ships for delivery to all points of the globe.

Osamu Kitajima sat across the table from his American lumberman

friend. He sipped his green tea appreciatively, holding the rough pottery cup

between his gnarled hands. The American sipped thick black coffee from a cup

made by the same local potter. “You make very good ocha, Frankran san,”

he said appreciatively.

Jim Franklin grinned. “Thank you Kitajima san. You have been

teaching us well these years.”

“You famery is well Frankran san?”

“Very well. My son is attending Vanderbilt Medical University in

Nashville.”

“And Frankran chan?”

“My daughter, Marci, is attending Berea College up in Kentucky.

She is a music major there. You should visit that college. The students are

from all over the Appalachian region. It was founded to teach students arts and

crafts and business so that they can know how to market their work. Every

student there, even if they can afford to pay their tuition must work in the

craft factories and in the stores that sell them. It is an interesting concept

and it has helped many young people out of the poverty of the mountains.”

“I must go there one day. And so, what music does she study.”

“She is studying the folk music of Appalachia. Her specialty is

the mountain dulcimer. Do you know dulcimer?” he asked.

“Durcimer?” the Japanese businessman asked. “I don’t know this

durcimer.”

Jim Franklin pushed the button on the telephone set.

“Yes Mr. Franklin,” answered the secretary.

“Bring in your dulcimer for a minute, please.”

A few minutes later the middle aged, slightly plump, secretary

entered the room carrying an hourglass shaped musical instrument about three

feet long. She handed it to her boss who lay it on the table in front of the

Japanese craftsman. “This is a mountain dulcimer. Some people say it has a

sound similar to one of your instruments, the koto?”

“Ah so desuka,” Kitajima said. “Can you play this

instrument?”

“Lula can play it beautifully,” Franklin said. “Please play

something for Kitajima San.”

The secretary shyly placed the instrument on her lap and began

strumming it. The Japanese man’s face grinned appreciatively. “The last time

you were here you gave me a CD of your daughter playing the koto,” she

said. “On that CD was a beautiful song and I have tried to adapt it to the

dulcimer,” she said shyly. “See if you can recognize it.” She began to strum

and the Japanese man’s face broke into a broad grin.” He hummed the familiar

Japanese classic as she played.

“This song is called ‘Chidori’. It is the song of little

birds dancing on the seashore. It is one of my favorite songs on the okoto.

Where can I buy one of this durcimer for my daughter?”

“We have a famous maker here in Townsend. I will introduce you to

him,” Jim Franklin said.

“Domo arigato, Frankrin san,” he said and he bowed

slightly over the table. “And now we must speak of business. What special woods

do you have for me this trip?” he asked.

“We just got in a Walnut tree that I think will be extra special.

They are clearing a right of way up in the park and it had to be removed.

Otherwise we would never get an old growth tree like it. I’d like to show you

the logs and if you are interested you can tell me how you want to have them

cut.”

“You always have special woods for me, Frankran san,” Mr.

Kitajima said.

Months after the walnut tree had been critically evaluated for the

best cuts to bring out grain and color, and had been reduced to various stacks

of finished lumber, it went to a building designed to slowly dry the wood to

prepare it for the final manufacturing process. When Jim Franklin was satisfied

the lumber had dried properly he packed it for shipment, fastening the packing

crate to pallets sawn from the smaller branches of the same tree. The pallets

of lumber were loaded by forklift on to railcars and they began their long

journey. By rail, they slowly made their way across the United States to

Seattle where they were lifted aboard a ship for the final leg of the trip

across the Pacific to Tokyo where they were transferred to a truck for the trip

up to Aomori to the Kitajima furniture factory.

As Kitajima removed each plank from the pallet, he ran his hand

over the fine grain and admired the warm chocolate brown color of the wood. He

felt the spirit of the wood struggle to get out. He would release it in his

creations. As a devout Shinto he believed that his own spirit and soul was

intertwined with all of nature.

Over time, the wide planks and thick pieces became low tables,

cabinets, and accent pieces for Japanese homes and a few exporters who had

wealthy clientele throughout the world. Finally, the stack had shrunk to a

small pile of scrap in one corner. It was time to contact the local woodcarving

teacher to come pick the rest so that his students could carve figures of

birds, animals and religious figures.

“This was a very useful tree, Kitajima San,” his foreman

said.

“Yes, so it was,” Kitajima said. “I must show my appreciation to

Frankrin San. He always saves the very best for us.”

That night, as Kitajima mulled over what he could do to show his

appreciation to his American friend, he heard the thin sound of a stringed

instrument coming from the Tokonoma room. He smiled. His daughter was

playing the instrument he had brought back from America, the mountain dulcimer.

Uki chan was an accomplished musician on the okoto, the Japanese

harp. She had studied the classic instrument since before she had begun grade

school. With help from the books that her father had purchased, and help from

her music teacher, she had been able to figure out how to play the dulcimer

almost immediately. Before long she had begun adapting classical Japanese music

to fit the new instrument’s style of play.

Mr. Kitajima had picked the dulcimer from among several which hung

on the wall in the dulcimer maker’s shop at the Craft Settlement. Although all

of them were the same hourglass shape, each was made of a different type of

wood: blond spruce, light yellow with dark ring sassafras, dark chocolate brown

walnut, and ivory colored alder. He had chosen one made from sassafras because

he liked the name of the wood as well as the sound of it.

“Where did you get this wood?” he had asked Bill the instrument

maker.

“I got that one from an old barn that was being torn down. I get

wood from many different places. I am always looking for old wood. Sometimes

I’ll find a board in an old barn. A lot of the old buildings around here were

made of hardwood. Even the fence posts were made of hardwoods. The instruments

I make from the old woods are much more valuable, but I also search for new

lumber at the lumberyard. As long as it can be worked down, it can be made into

a good instrument,” Bill had explained.

“Ah soka!” Kitajima said. An idea began to grow in his

head. Frankran san’s daughter was studying the traditional music of the

Tennessee mountains. He picked up the phone and dialed a friend who made

traditional Japanese instruments such as the koto, shamisan, and shakuhachi.

After his required pleasantries and polite greetings, he explained the reason

for his call. “Sensei, I would like to commission you to make an

instrument for the daughter of my friend in America. It is called a dulcimer. I

will bring my daughter’s dulcimer to you so that you can see how it is made. I

will also bring you wood from my friend’s mill so that it will have very

special meaning. I wish to deliver it on my next trip to America.”

Kitajima san used the same crate and the pallet the walnut

had been shipped in to pack an order of wide clear planks of the special wood

that grew on his property near the river. In his language it was called “ho”

wood, a special kind of cottonwood that had even fine grain but was soft and

easy to carve. It was a favorite carving wood for Japanese students learning to

carve. He had introduced the wood to a woodcarver friend of Jim Franklin in

Tennessee. The Americans used basswood for their carvings. The ho wood

would provide an alternative.

Once again, the pallet and crate made its journey across the

Pacific and overland across the United States until it finally was delivered to

the woodcarving shop at Nawgers Nob, less than a mile from where the crate and

pallet’s journey had begun. The crate was opened, the ho wood removed,

inventoried, priced and put on the shelves to fill orders that came in by phone

for items from their catalog. After the now beaten up crate was empty, it and

its pallet joined other broken crates and pallets behind the shop. When enough

wood accumulated, it would be hauled off to be ground into mulch. Some would

become firewood if the weather turned cold.

Bill the dulcimer maker, always on the lookout for wood that he

could use in his instruments, saw the new additions to the pile behind the

woodcarvers shop. Usually pallets were made from trash wood or oak, but he

occasionally found red cedar or mahogany used in a pallet. With his

pocketknife, he shaved through the rough surface and exposed the wood beneath.

A rich brown shone through. He wet his finger and swiped across the surface and

the fine grain shone through. It was walnut. “It might be usable wood, never

can tell.” He noted the stencil marks and painted numbers and stickers that

hinted at the distances the crate and pallet had traveled. “If you could talk,

you could probably tell some mighty interesting stories,” he said.

In his shop, Bill removed all screws, staples and nails from the

pallet. He ran each narrow board through his planer to remove the rough surface

and dings from steel strapping and from being banged into by other crates. Each

board revealed the hidden beauty of the walnut hardwood. Bill ran one board

through his saw, shaved off two quarter of an inch thin sheets and placed them

side by side. The effect, called bookmarking, showed the grain in a mirror image

with each growth ring meeting in the center. He ran the two sheets through a

sanding machine working them down to an eighth inch think. This is the finest

walnut I’ve ever seen, he thought. If you sound as good as you look, you will

be a remarkable instrument.

Bill cut the fretboard, sides and top from other planks in the

former pallet. To get a thick enough piece for the neck, which held the tuning

machines, he laminated several layers of the wood. He cut a graceful scroll on

the end and sanded the neck to a fine finish. This neckpiece he took to his

friend the woodcarver.

“This is a remarkable piece of wood,” the woodcarver said, when he

saw the neckpiece.

“Can you carve a wood spirit on it?” Bill asked.

“I think I can do that. You can almost feel the spirit in the

wood. I might not have to do much of the work. It might reveal itself on its

own.”

Bill and the woodcarver looked down at the finished mountain

dulcimer. The rich wood shone through the layers of lacquer. Inlaid

mother-of-pearl rimmed the edge. The rosette shaped sound holes were also

ringed with pearl inlay. Pearl dots denoted major fret positions on the fret

board. Bill strung each of the four strings and tuned them.

“Sounds good Bill,” the woodcarver said.

“So far, so good,” Bill said.

He took a pick from the drawer beneath the workbench and began

strumming a slow Appalachian melody followed by a rapid rendition of a familiar

fiddle tune. Putting away the pick he began plucking the strings with his right

hand while he formed simple and then complex chords with his left hand. He

changed tunings and called on his vast repertoire to test each one.

“My, my,” the wood carver said.

“This one isn’t for sale,” Bill said as he wiped his eyes.

The Christmas season was busy for the Dulcimer shop. Bill depended

on a supply of inexpensive dulcimers from several mass producers in Ohio,

Kentucky, Tennessee and South Carolina, but their inventories were also thin

during the holiday season and because of a revival of interest in the

instrument. Bill could hardly keep enough instruments hanging on the wall to

give his customers a choice. The handmade instruments Bill labored over in his

shop were ordered weeks and sometimes months in advance. They never appeared on

the wall. He would not cut corners or rush an instrument just to push out more

product.

The wall was bare late in the afternoon and Bill prepared to close

the shop a few minutes early to join his family on Christmas Eve. The door

opened slowly and a stoop shouldered old man stepped timidly into the shop.

Bill didn’t recognize the thin old man. His work overalls were

clean but threadbare. His gray hair was covered by a worn felt hat, which he

held nervously in his hand. His grizzled face was creased into a facsimile of

the hills and canyons of the Smokies from which he had undoubtedly come.

“I hope I’m not keeping y’all,” the old man drawled when he saw

that the shop had been prepared for closing.

“Not at all sir,” Bill said. “It’s been pretty quiet this

afternoon. I guess most people have headed for home for the holidays.”

“I won’t keep you long, son. But I hope you can help me. I’ve seen

your sign out there for years and never came in to see you, an I hope you can

forgive me of that. But until recently I didn’t have a need a yer bidness,” he

said.

Bill came out from behind the counter and pointed to the rocker in

the corner of the store. It was armless and a favorite place for customers and

friends to sit and play his dulcimers.

The tired and frail old man gratefully accepted the chair and

leaned back to unkink his bent back. “Thank you, son. I ain’t as good at

standing around as I used to.”

He looked furtively around the shop, eyes searching. “Nearly 90

years ago, I used to play in a big walnut tree near our farm. They was a little

neighbor girl and me would sneak off there and climb in it. We’d a got a

whippin if our parents had a known we was a doin that cause they warned us to

stay out a trees cause we could a hurt ourselves. Well we went there and played

when we could and when we got to be sparkin age we just naturally kept going

back there.

“Well, y’all might a guessed it eventually, but we have ended up

spending the next 70 years married and raisin younguns. When we got married, we

was dirt poor. We couldn’t a afforded to get married ifn the preacher had

charged us. I wanted to give her a gift that was fittin for her and the

occasion. The summer before, I had found a branch that had been broken off that

tree during a snowstorm in the winter of ’23. It was the same tree we’d played

in and courted in and I got an idea to use it to build her a dulcimer. They was

quite a few of them around in them days and they was all homemade so it wasn’t

hard to get some help from a neighbor who had made several of ‘em. We took that

branch to the mill up in Cades Cove and had it cut down as thin as they could.

We used a plane to get the wood thin enough. It wasn’t as fine a job as you do

now a days, but we was pretty proud of our handiwork and it sounded real good.

“Well anyhow, my bride loved that little box. She learned to play

it real good. As I said, we had a passel of younguns. Out a 10 of um we have

out lived em all. Now it is just ma and me up in the cabin in the hills. We’ve

lived there all these years through good time and poor. We don’t need much now and

we get along pretty good on our social security. But the other day is when it

happened. This is what I been working up to.

“You know, ma loved that music box and she would play it all the

time to fill her loneliness. And then this guy came by the house and said he

was looking for stuff for a museum. We tol him that we didn’t have no stuff for

a museum, but he spied ma’s dulcimer and he said that it would be perfect, how

much did we want for it. Well I told him it weren’t for sale and ma reminded me

that if I didn’t get my eyes worked on then I’d go blind and where would that

leave me. I got cataracts, you see, and it cost a pretty penny to get a doctor

to cut them off right. So ma asked the man what he was a willin to pay for that

dulcimer. I repeated that it weren’t for sale but she is a stubborn woman. He

said he’d pay a thousand dollars for that old homemade insterment. I still tol

him it weren’t for sale, but ma handed it to him and said ‘take it.’

“Well the man was good for his word and he gave her ten one

hundred dollar bills and wrote out a bill of sale to prove we hadn’t robbed a

bank or somethin and he left.

“Well I got my cataract cut out but it ain’t the same at home. Oh

sure, I can see purty good now, as fine as an old man has a right to, but I

ain’t seeing no light in ma’s eyes no more. She misses that music box so much.

So I made up my mind to make her another one, but when I went down to that old

tree she was gone. Lectric power line goes through there now. They cut it down

and left a big ugly gash through the woods. So I came here to you.

“I’d like to buy a dulcimer for ma. You got one back there that

ain’t been hung up yet? I don’t know how much you charge for them and I don’t

know ifn I can afford it or not, but maybe you can take payments.”

Bill sat quietly, caught up in the old man’s story. He had no

dulcimers for sale. Bill Franklin had told him about an old walnut tree that

had been removed from the right of way for the power line.

“I’m sorry sir, but I sold the last one this morning. I’ll get

more in, in a few days.”

“I was hopin to make a surprise for ma this Christmas. It would be

the best Christmas ever, for me, to get that light back to shinin in her poor

old eyes,” he said sadly.

“Maybe I can help you,” Bill said. “Wait just a moment here.” Bill

walked into the backroom workshop. On the wall hung the walnut dulcimer made

from the packing pallet. It was as near a perfect instrument as he had ever

made and he was very proud of it. If he had decided to sell it, he could

command top dollar from either a collector or a concert musician. He took it

down and lovingly caressed the back and sides. He tested the tuning and carried

it back to the storefront. The old man remained in the rocker where he had

rested while telling his story. “I do have this old dulcimer here that I could

let you have. How much did you have in mind to pay for one?”

“Well it ain’t much, and I wouldn’t want no discounts or anything,

but I got 35 dollars left over from that cataract operation. Is that enough for

a down payment?” He asked.

“Tell you what. This old dulcimer is what we call a second. It has

a slight defect and I can’t sell it. What say I give it to you for what I got

in it, you know, strings and tuning pegs and such,” Bill said.

“Well I don’t know, son. What kind of defect are you talking

about? Do it sound good?”

“Oh yes, it sounds good. If I don’t tell you about the defect you

probably won’t find it. If I show it to you it will grow on you,” Bill said.

“Sounds sensible, how much you got in it?”

“About 35 dollars,” Bill said.

“How about you play something on it so I can be sure it sounds

okay,” he said.

“Your wife got a favorite song?”

“She always played one for the little ones when they were fussy,”

he said. “If you will hand it over to me, I’ll see if I can pick it out for

you,” he offered.

Bill handed him the magnificent “defective” dulcimer and the old

man positioned it on his lap. His gnarled left fingers pressed the four strings

and with his right hand he softly plucked the melody as he softly sang,

“Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound that saved a wretch like me…”

When he finished he handed it back to Bill. “It sounds nearly as

sweet as the music box that I made out that old walnut branch. Could a come out

a the same tree. I could a swore that this spirit carving just winked at me.

I’ll take it if you are still a mind to sell it.”

“I wouldn’t have it any other way,” Bill said as he enclosed the

instrument into a case for which he normally charged 35 dollars.

No comments:

Post a Comment