For a Christmas tree, Philip and I pruned a pine branch that hung over the sidewalk leading to the house, put it in one of Lora’s Ikebana vases and tied it flat against the wall. We referred to it as our Ikebana Christmas tree.

Janelle folded paper origami cranes and other bird-like figures and hung them on the tree to supplement the few ornaments we had carried to Japan.

One of the students had made a tape of Christmas carols for Mr. Uramatsu’s Christmas party. I had made a copy of the tape, and we listened to it repeatedly as we wrapped the gifts. When we finished, the floor around the tiny tree was covered with gifts. We actually hadn’t bought many of them. Most were from the children’s friends, people at the college and a box from home sent by Cinda.

I had just finished my bath, and Lora was taking her turn at the ofuro when the phone rang. “Hello,” I answered. If I were to use the Japanese phone greeting of “Moshi, moshi,” the caller might think I were fluent enough to speak in Japanese.

“Herro,” a male voice said.

I waited for a moment for the voice to continue, but it did not. “Hello,” I repeated.

“Herro,” it repeated. I could tell the caller was male, and I could hear store sounds in the background.

I waited for a while longer. I was almost ready to hang up. I assumed it was a crank caller or one of the calls we occasionally received from someone on the other end who lost his nerve after hearing English.

I said “Hello,” once again.

“Herro, Kitaura here,” he said finally. He paused again. If it were the Kitaura we knew from Chinzei, he could speak only a little English and only when he had quite a bit to drink. “I come your house.”

“Tonight?”

“Yes. Good-bye!” He hung up.

I didn’t know what to do. Lora had wanted a quiet evening at home. I told her about the phone call, and she cut her soak short. We thought perhaps like Mr. Nakano, Mr. Kitaura would stop for a moment and leave again. I had also given him a Christmas card. Also I didn’t know from where Mr. Kitaura was calling. He lived in Nagasaki nearly an hour away by train or bus. He could have been calling from Nagasaki or from Chinzei.

A half hour passed, and we still waited. Philip and then Janelle took their turns at the ofuro. At 8:30 the buzzer sounded, and I opened the door to find Mr. Kitaura standing outside, balancing a large boxed Christmas cake in one hand and a bag of bottles in the other.

“Merry Kurisimasu,” he said. He handed me the box. I invited him in. He kicked off his shoes, donned slippers and pushed his way into the living room. He had been there often before on school business and knew his way around. He promptly sat down in the middle of the floor on the carpet and began taking the five bottles of juice and three quarts of beer out of the shopping bag. He lined them up in front of him and then opened the cake box to take out a large white cake decorated with a cookie house, candy Santa, candy tree, the words Merry Christmas and a packet of candles.

Lora and the children gathered around Mr. Kitaura to pose for pictures, then he insisted I join the family while he took pictures.

Through all this no English words were exchanged. Mr. Kitaura did not speak English except after drinking, and he had not begun that yet. For most Japanese men, it was necessary to relax the tongue with a few beers before they lost their inhibitions, then alcohol could be blamed for any mistakes in grammar or pronunciation.

Janelle cut the cake and set a plate in front of him but he didn’t touch it.

“Keki wa tabe masu.” (Eat the cake,) Janelle said.

“I drink, no eat, Japanese Christmas party,” he laughed. He spoke rapidly in Japanese to Janelle. She understood and answered in Japanese.

I understood neither the question nor the answer. She went to the kitchen for glasses and an opener.

“Nijuu hachi, to my house?” he asked Philip. He had made an arrangement for the children to go to his house in Nagasaki on the 28th to meet his son and daughter who were the same ages.

“Yes,” Philip said. “We meet you at Nagasaki station.”

“Yes. Come back Chinzei, taxi. I bring,” he said.

“Put them on the train,” Lora said.

“We, Janelle, me, go train, Nagasaki, very easy,” Philip explained to Mr. Kitaura in his own brand of special English.

Kitaura listened and asked a couple of questions in Japanese. Janelle answered. He shook his head and said. “Taxi better.” A one-way trip to Nagasaki by taxi cost nearly 5,000 yen or 25 dollars. He drank his beer and poured for us. We sipped while he drank deeply.

Janelle brought out a Japanese card game, and he instantly took charge of it. The game consisted of two sets of cards; one set was spread out on the floor. Each card had a picture and a hiragana symbol as a clue. The leader read from another card, which contained the description of a card on the floor and had the hiragana sound as a clue. Lora, Philip and Janelle had been studying the writing system every day and had an advantage over me. I had studied them and memorized them and had forgotten them several times.

Kitaura read the Japanese, and we searched for the matching picture card. Philip recognized most of them first, and Mr. Kitaura began trying to arrange it so that Janelle could win at least one. He roared “Goot! Goot! Goot!” each time anyone recognized the hiragana. “Jōzu ne!” (Very skillful,) he would say and point to the winner.

“Japanese Christmas party,” he laughed many times. It was nearly ten thirty when the game ended. We sent the children to bed, “to wait for Santa,” we told him. I thought perhaps he would take the hint that it was getting late, and he should make his way home to Nagasaki. At the faculty party at Shimabara, he had become a little too bold with Lora after a certain point in the evening and after he had a certain amount to drink.

“I hope... I want you stay Chinzei... two year...,” he said.

I smiled and nodded. We had already decided to stay only for the one year originally contracted, but it wasn’t a good time to tell him.

“I am sorry... visa paper,” he said.

I wasn’t too sure what he was talking about. He had been in charge of our papers, which were two weeks late in arriving in the summer. Perhaps he was trying to tell us he was responsible for the lateness and was sorry. Maybe he was talking about Bill’s papers, which had come the last day before he almost had to leave the country.

“Mama san, sing White Kurisimasu,” he said. While we visited, the tape played in the background. When either “Silent Night” or “White Christmas” came on, he’d break into song, perfectly imitating Bing Crosby’s voice and inflection. “Bing Crosby,” he said. “‘White Christmas, I’m dreaming of a white Kurisimasu....’” his voice was deep, strong.... “‘just like the ones I used to know...’ In Japan, no white Kurisimasu for you... I’m sorry.”

As we listened to the music, and he sang, Lora got out the children’s stockings, a couple of large wool socks that had red and white trim she had bought that morning.

Kitaura was fascinated as he watched Lora fill the sock. In his notebook, he listed everything Lora put into the stockings: peanuts, a couple of Australian kiwi fruit, a small package of English walnuts, origami paper, stocking stuffer toys, candy and a mikan orange. The more Lora stuffed into the stockings, the more excited Kitaura became. He pulled out his wallet. “I am Santa,” he said. He stuffed a one thousand yen note into each sock. “For books,” he said. “Phirip kun bery goot hiragana. Phirip kun good ping-pong,” he said, using the familiar term for boys, “kun”, instead of the more formal “san”.

Philip played table tennis during his study and lunch breaks and had begun earning a reputation at Chinzei.

“I ping-pong champion, Kyushu,” he said proudly. He pointed to his nose, a gesture with the same meaning as pointing to yourself in the chest with your thumb. “I want go America. Play ping-pong champ. When I am in college... not study English... play ping-pong,” he laughed. He checked his notebook and read down the list, “peanuts, kiwi, walnuts, mikan” We had to spell the English for some of the words, and beside each, he wrote the katakana sounds for his further reference. “I make my kids.”

Lora hung the stockings on the back of a chair near the little tree.

He applauded gustily, “Very good. Santa Claus Mama,” he laughed.

It suddenly began to get quite cold in the room. Both kerosene stoves were out of fuel. Our reserve fuel cans were also empty. We had not planned to be up so late and had thought there would be enough fuel to last until about noon on Christmas day. Unfortunately, the fuel delivery would not be made on Sunday. Lora pulled a coat on over her sweater to keep warm. Kitaura seemed not to notice the cold.

He poured again, “Japanese Kurisimasu party. Drink. ‘I’m Dreaming of a White Kurisimasu....’” he glanced at his watch. It was past 11 p.m. “I must go back home, Nagasaki,” he said.

“How do you go home?” I asked. “By train?”

“No, by car.”

“Do you drive?”

“No. I am drink. I go taxi.”

He continued to sit in the same spot he had occupied all night, the empty bottles of beer to his side, the last glass of beer in his hand. He was a middle-aged man still in his business suit. He was tall, a little heavy, robust, his head was shaved. He had a round face with very oriental eyes and high cheekbones. His cheeks were quite flushed from the alcohol.

He glanced at his watch again, but made no move toward the phone. “You must learn Nihongo-Japanese language,” he said. “In office, girls, men, no can’t speak English. ‘Tegami’ you say. Don’t know you want. You must Nihongo. I teach. OK?”

“OK,” Lora said. He coached her on what to say to the office girl when asking if the mail had come or when we needed to order propane.

Lora repeated his phrases to his satisfaction.

The tape of Andy Williams made it around to “White Christmas” again.

“Sing mama, papa,” he said. We all sang with Andy for probably the tenth time that night. The song ended, and he checked his last bottle of beer. It was empty. He stood, “I must go Nagasaki.”

“Shall I call a taxi?” Lora offered.

“No. I call,” he said.

He hung up the phone and rejoined us in the front room to inspect the stockings and the stack of gifts under the tree. “Very nice Japanese Kurisimasu party,” he said. “Now I go home Nagasaki,” he said.

We led him to the front door. I started to put my shoes on to see him to the street where the taxi would pick him up, but he insisted I stay in the house. It was cold out, and it had begun to drizzle a little as he walked unsteadily up the steps. I watched until he got to the street almost at the same time a taxi pulled up.

Lora and I picked up the empty glasses and empty beer and juice bottles and put them in the sink. “I think he sensed we were a long way from home and just wanted to be sure we had a party,” I said. “I’m sorry you didn’t have Christmas Eve with just the family here.” I half expected her to be a little angry.

“Bill said the Japanese celebrate Christmas by getting people together and having a party like a New Year’s Eve party,” Lora said. “I thoroughly enjoyed our little party. I am so touched by his thoughtfulness. The cake box came from Nagasaki. He came all the way from Nagasaki tonight and spent a lot of money and still has an hour to go to get home,” she said. It was then 11:45 P.M.

As usual, the children were up early Christmas morning. The house was colder than usual, as there had been no oil left from the night before. Philip took the container up to the dormitory to ask if he could borrow a little from Mrs. Yokoyama and soon returned with a full five gallons. With the fire lit and the room beginning to warm up, we began to open the gifts.

As usual, Lora had lost all self-control and had stocked the kids with socks, sweaters and other clothes. Janelle and Philip had done their shopping a few days before when we went to Nagasaki and Toshio Mita had helped them to find the stores and the bargains.

Lora and I settled in with our instant coffee and watched as the children each selected gifts and began carefully opening them. Their slow, careful start was in marked contrast to other Christmases when they’d ripped them open with frantic abandon and looked up in horror to ask “is that all there is?” They opened their presents and seemed very satisfied with everything when they were done.

Many of the gifts were from school friends and from the teachers at Chinzei. When all were opened, there was a large assortment of clothes, eats and books. The children were already reading their books sent by Cinda. Lora thumbed through a big volume of “Complete Course in Japanese Conversation” a gift from Kiyru sensei.

The last package was one that had been given to us by the Cobleigh Cultural Center where we taught the night class. Michiko Nonaka had handed it to me a week before with the comment, “Perhaps it’s meat.” I had opened the end of the wrapping and read, “ITO HAM PACKAGE.”

The stores were filled with packages of food which were to be given as year-end presents. Presents of ham, fish, dried mushrooms, canned fruits, tea, coffee and soap were attractively gift-wrapped. Because they sat on the store shelves for some time, they were nonperishable until opened. I had opened the package far enough to be satisfied it was nonperishable when I saw the canned ham label.

I slowly removed the paper and was greeted by a faintly rotten smell. Inside the ham box were six slices of beef–six large three quarter inch thick beefsteaks. They smelled putrid. I separated them one from the other. All were thoroughly spoiled. Apparently, they had been frozen and had thawed, which added to their decay. We hadn’t seen so much beef since we’d left Oregon.

Lora and the children joined me for a good cry. I slowly took the box outside and buried it. Beef cost about $25 a pound, and I estimated each steak weighed nearly a pound. Perhaps the hardest part would be when we would have to smile and thank the Cobleigh manager very much for the delicious steaks the next time we saw him.

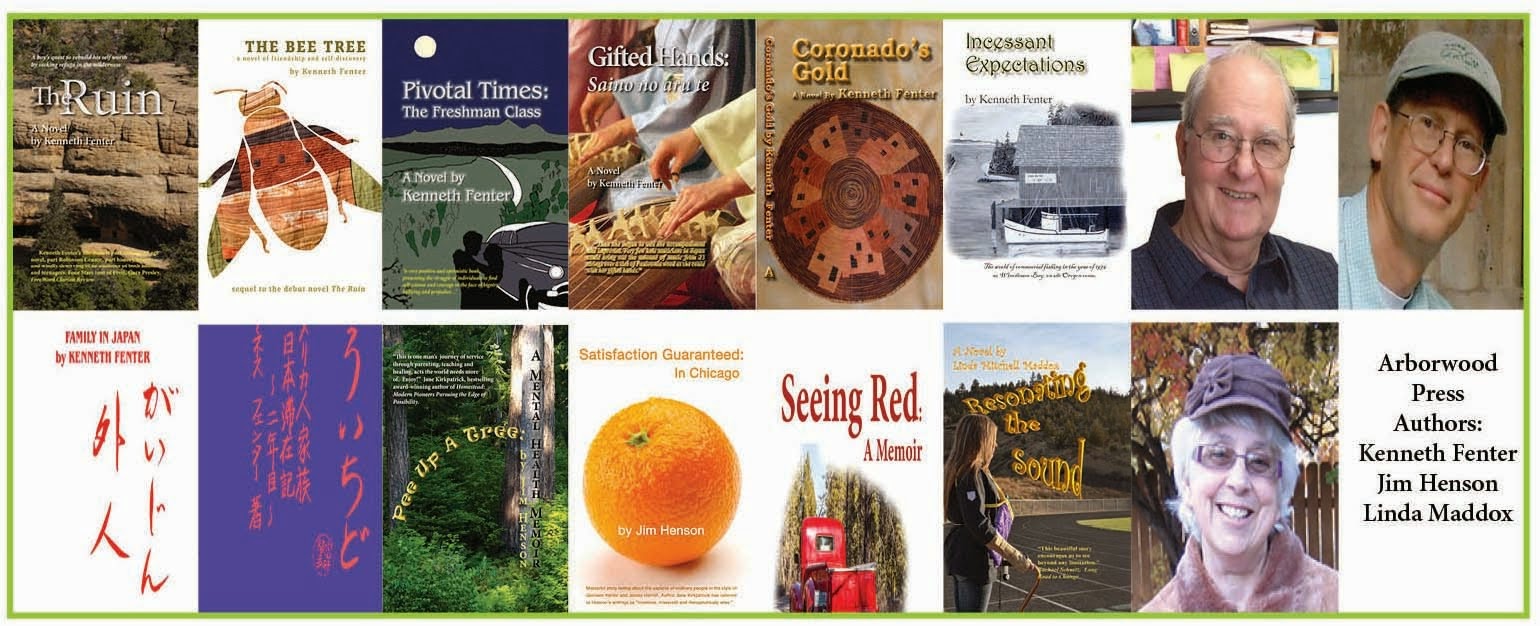

This story is taken out context of the book and so a quick note on the role of alcohol in Japanese culture: The consumption of alcohol in Japanese society is spoken to in much more detail in the book Gaijin! Gaijin! It was our observation, and according to the books we read, alcohol was used to overcome habitations or to relax the very strict social rules which people lived and worked by daily. Under the influence of alcohol individuals were excused for their manners and recriminations for violations were few with exceptions. Laws could not be violated. One could not drive while intoxicated, for example, or commit crimes. One could however, be impolite, speak English without worrying about making mistakes, call without making appointments, tell their boss what they think etc. however.

Have a joyous holiday season and a positive New Year!

Respectfully submitted,

Kenneth Fenter

No comments:

Post a Comment