Last night we watched the million revelers bundled against the cold and the ball drop on Times Square

as the clock there struck midnight ushering in 2011. It was convenient to those of us on the west coast

as we could turn in shortly afterward and get up early to watch the Rose Parade.

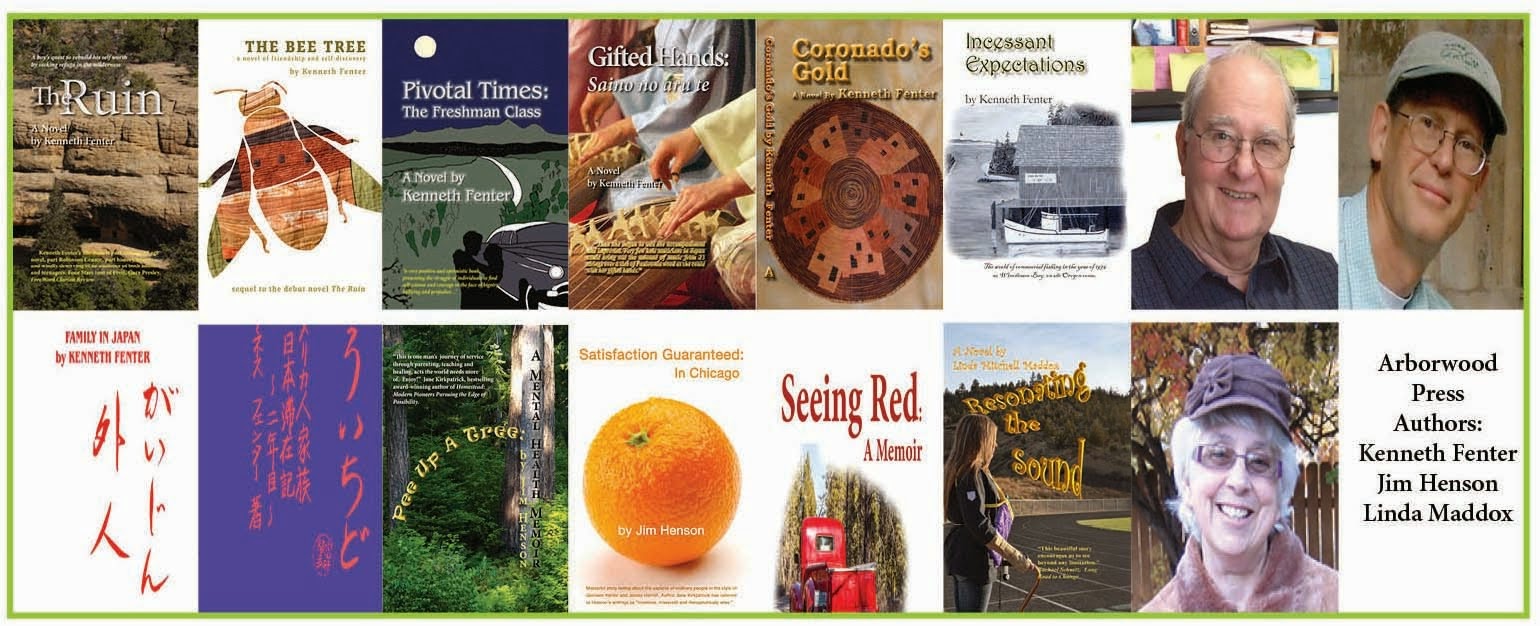

My thoughts this morning, this New Year's morning 2011 to New Year's morning 1978 at our home in Isahaya, Japan. I thought I'd share that occasion with you. Following is the chapter from my book Gaijin! Gaijin! The photo is of Janelle and students at Chinzei Gakuin taken a couple of nights before at the college making mochi, a pounded glutinous rice and patted into rice balls which were used as part of the New Year's celebrations.

Chapter 44

While Christmas to the Japanese was more of an excuse for a party than a religious observance, New Year’s loomed as the primary national holiday: part religious, part traditional and part superstition. Although it seemed impossible to push another customer into department stores, the crowds continued to grow in density, and the shopping pace became more frantic.

The week between Christmas and New Year climaxed the oseibo (year-end gift exchange.) The gifts were from household to household; children presented a gift to their parent’s household; employers sent gifts to employees; students of traditional arts to their teachers; the parents of apprentices to the master artisan; patients to doctors; and on and on. Often, the person receiving the gift sent a return gift.

Big department stores such as UNeed, Nichidai, Okamasa, or Hamaya devoted major space to displays of year-end gifts, and a host of specialty stores had suddenly appeared around the first of December to capitalize on the season. Attractively arranged gift wrapped boxes with a variety of food such as canned hams, dried mushrooms, dried fruits, dried persimmons, fish, small jars of varieties of coffee, varieties of tea, jars of flavored sugars, packages of unusual delicacies, candies, even packages of bar soaps, and towels were available for year-end gifts. Because they usually consisted of several different varieties of mushroom, or ham, etc. they were called gift sets. Stores attached coupons to the samples, to be filled out by the customer with the name of the recipient and their address. Customers paid for the respective gifts, and the store would deliver them, with appropriate messages, by January first.

Several times during December, Bill had come to school hung-over and sleepyeyed from a year-end party the night before. “It’s kind of interesting, but it’s one of the times I glad I’m not Japanese. Some of my friends have been to a party almost every night,” he said one morning. “People just seem to like to get together and renew friendships, and if they’ve had any disagreements it seems to be a time to forget about them and let bygones be bygones and repay any kindnesses received during the year. I guess it’s really complicated,” he laughed, “knowing what obligations have been incurred during the year. Boy I’m not sure how many year-end parties I could take.” He rubbed his temples and made another cup of instant coffee. “You know, people here must keep a journal of all their social obligations,” he laughed.

“You might want to write down the greetings you should give on New Year ’s Day,” he said. He wrote, Akemashita omedetō gozaimasu kyūnen chu wa iro to ōse wa ni narimashita honnen mo yoroshiku onegai tashimas. “This means, ‘New Year congratulations! Thank you for your kindness to me throughout last year! Please give me your kindness during the present year.’ If you can’t remember all that, just say the first three words.”

The post office sold special cards with a lottery number printed on the bottom. They either had pre-printed greetings or were blank for the purchaser’s personal message. The post office held the cards and delivered all of them on New Year’s Day. Television and newspapers announced the winning lottery numbers, and card recipients checked to see if they had received a card worth a few cents or hundreds of dollars. We usually received our mail at the college, but that day a bundle of cards were delivered to the door. The logistics of collecting cards for every household in the nation and delivering them all in one day, must have been horrendous. I had seen people buying cards by the hundreds for businesses to send out to customers, so the volume was extraordinary.

Mrs. Tsunō warned us to stock up on food and necessities such as heating oil, as everyone, including the housewives, would be on holiday from January first to the third. Even the dairies took time off. We asked about what happened to all the milk and eggs, but never found out.

Saturday morning, New Year’s Eve, Toshio called from Nagasaki to ask if he could call on us. When he arrived, he carried two loaded shopping bags. After he congratulated us on the purchase of our new kotatsu (our family Christmas gift to ourselves) and was comfortably seated at it and served tea, he began unloading the shopping bags and explaining the contents.

“New Year is the most important time for us,” Toshio said. “So Yoko and I thought I should come here and teach you about this important custom. Some of it is religious, and some is superstitious. If you believe in superstition perhaps it will be beneficial to you too,” he laughed.

“This week my family has been cleaning the house. You have the custom of spring housecleaning. However, we must clean out all dust of the old year, and the clothes must be washed so we can welcome the New Year in fresh clean garments. And if I have any debt, I must repay it. Of course, it is not the law, but if I have some unpaid debt my reputation may be damaged,” he said.

“You will hear the temple bells ringing tonight, and you must complete all your duties of the year before the bells finish ringing 108 times. Well, you know, there are 108 misfortunes that may befall you in the year. The ringing of the bell is similar to baptism of your Christian religion. When the tolling is finished and the New Year begins, everyone begins again. Because you begin fresh, you must observe many things to be assured success in the New Year. For example, please don’t sweep your house on the first day or you may sweep out the good luck. And you should not be unpleasant or have a quarrel with your family or you will have a year of unpleasantness. To assure happiness we have many games that we play to keep amused and happy.

“If you watch you can see your fortune. If your first caller has a good reputation and much money, you will have good fortune. But I pity you if the first caller is a beggar,” he said quite seriously. “And the night of New Year ’s Day is very important, because you must have good dreams to begin the year. If you have a nightmare, your nights will be sleepless all year.”

From his shopping bags, Toshio took out paper or plastic ornaments that were symbolic decorations to be used for New Years. On the table, he put a small set of decorations called kado matsu, a sprig of pine backed with three stalks of bamboo. “This smooth bark stands for the female, and this rough bark stands for the male. You should place one on each side of the gate, or if you have no gate, then on each side of the door. The temples will have a very large version of this decoration. This pine tree means long life, and the bamboo is for virtue. The word for virtue is a pun on the name for bamboo. And here is a sprig of fern. It has many leaves, so it means good fortune throughout all the days of the year.”

Another decorator item consisted of two white mochi cakes. They had been round when fresh, and one was smaller than the other. The small one had been attached to the top of the larger, and both had dried into a hard cake. “This is called kagami mochi. Kagami means mirror, and mochi means long life. It represents the sacred mirror of the Emperor. It should be put in the place of honor in the tokonoma.”

Next to come out of the bag was a plastic lobster. “This lobster has a bent body like the old man. For New Year, it means long life. But the lobster has a bent back even when it is very young, so it means to have youthfulness even with old age. And you must have this orange. It is a very special bitter orange called the daidai. That word is a pun as it means the same as the Chinese word for generation to generation.”

Last to come out of the bag was a beautifully lacquered three tier box. Boxes made to carry lunches were called obento. These could be simple throw away boxes that one picked up at the train station or bus station kiosk, or it could be a more permanent box of wood, plastic, or metal that a person carried each day, the equivalent of the western school lunch box, or brown bag. Obento were sectioned to help keep portions separate. Usually, they had a large space for rice and sections for a piece of fish or chicken, beans or vegetables, pickle, a slice of pink fish protein cake called kamaboko and some seaweed strips called konbu. Most of the foods were selected for their ability to stay fresh without special refrigeration.

“Well, you know, in Japan it is the daily task for the housewife or mother to cook for her family. There is no vacation from this task. Even on the holidays people must eat. But on New Year’s, even the housewife must have a vacation, so today the housewives of Japan are cooking a special lunch box like this that will have special foods to last for the three days. The first meal we will have is very important. Yoko will serve a dish called ozone. It is a soup with mochi and vegetables.”

He opened the top tier of the obento. Inside was an assortment of foods, prepared and arranged much too prettily to disturb. “This is special rice called sekihan with red bean. Here is the meat of the carp. This fish is very strong and has great determination and long life. These black beans have the same name as the word that means robust. And here is konbu sea weed for happiness and lotus root which is considered a sacred plant. And Yoko has added some red radish cut like a flower and a boiled egg made to look like a bunny and some greens to make it more beautiful. These foods, you can see, have special meanings. Yoko and my mother made these sample obento for you. Of course they are just a sample. For our family, it is more extensive as we must take all our meals for three days from this obento.

“Of course, to have the days of vacation, Yoko and my mother have to work extra hard to cook these special obento. Everything is very pretty, of course, and so it takes a long time to cut this egg to look like a rabbit. Or this radish to look like a flower. So Yoko complains it takes three days to rest up from preparing for it,” he laughed.

We admired the layers of the obento and appreciated the extra hours required just to prepare the sample.

“Of course besides this, we must be prepared for many guests. You may have visitors tomorrow. It is customary to visit your friends. If they come, please offer them tea. If you have some snack to offer, it is O.K. I think you don’t have to worry about it. It is a quiet day, and you will be interested, I think,” Toshio said.

“Tonight if you want, why don’t you go to the temple and help to ring the bell. There are many temples in Isahaya. You may go to any of them. The bell must be rung 108 times, one for each vice.”

“Is that right?” Lora interrupted. “One hundred eight vices? We have been taught there are only 10. We Westerners must be missing a lot!”

“Well, you know, there are many misfortunes in life. The 108 are said to be the vices and misfortunes. After the bell has been rung, then you must be careful to avoid misfortune in the future. When you ring the bell you may be disappointed. You know the temple bell in Japan is different from those in your country and in Europe. It is cast to make the after-sound, not the initial sound. You see, it is most beautiful to hear the sound as it begins and fades and after it is gone, the silence is heard too. You must experience the silence as well as the sound.”

When he prepared to leave he said, “The ornaments are for your souvenir of Japan. The obento boxes are real lacquer-ware and are our family treasure. They are to be considered a loan. Please save them for me, and I will collect them when you have eaten the sample.”

That night the television networks featured special variety shows for the countdown to midnight. NHK had the most elaborate program with most of the nation’s top popular and traditional singers who formed into two groups and competed good- naturedly for audience approval.

There were several different levels of music: popular rock and roll with clean cut young men and women, many still of high school age; older singers who had graduated from hard rock music and were becoming the more mellow professionals who sang the popular songs that were imitated by business men in the singing bars; and the traditional singers of all ages who kept the traditional folk-music alive.

The young rock singers were dressed in everything from tux to drag. The middle group dressed in a variety of fashions with many of the women in kimono while the traditional group, men and women, wore kimono or the dance costumes associated with particular folk dances and songs.

The entertainers divided into two groups who competed by doing songs and comedy sketches. The studio and home audiences voted for their favorites. It was designed to culminate at the stroke of midnight. During the program, the network stations would feed live reports on New Year activities around the country, spotlighting local customs.

In the mid-evening Philip, Janelle and I went to a temple in town and joined the people who wanted to ring the bell. In the courtyard of the temple, a small bonfire burned to warm the visitors. People lined up to take their turns. A small square tower held the bell which was thimble shaped rather than flanged at the bottom. The bell hung in the center of the tower.

On one side of the bell, suspended from lines attached at both ends and to the ceiling, hung a pole about six inches in diameter. From the center of the pole, a single rope hung to the platform. Visitors grasped the rope, pulled the pole back from the bell, then swung the pole against the bell as forcefully as possible producing a dull gong sound.

Visitors straggled in and joined the line, gave their turn at the bell, ringing it once, then moving on out to give the next person a try. Although it was to be rung 108 times, no one seemed to keep count.

On our way to and from the temple, we passed by other temples where people rang that temple’s bell. Although the bells ranged from 24 to 48 inches high, they produced relatively little sound. Wood on metal and the thick wall of the bells produced a quiet, muted gong and sustained reverberation rather than a loud piercing clang as produced by a metal clapper. They could be heard close to the temple, and there were temples scattered all through the town so one could hear a bell ringing from almost any place in town, but not a great deal of overlapping sound.

New Year’s morning the town was quiet. The sounds of buses, cars and trucks, that usually created a buzzing presence even away from the highways, was absent. The wheels of industry and commerce had stopped. The crowds were gone from the stores. The world seemed to have stopped.

Early in the morning, I rode to the large temple at the foot of Isahaya park, next to the Megane Bashi stone bridge. Even early in the morning, with a touch of frost still lingering, men, women, and children were strolling from town to the temple.

At the main gate were large versions of the bamboo and pine arrangements that Toshio had brought for the entryway. A six inch diameter braided rice straw rope hung from the cross bar of the torii (gate). People rinsed their mouths from a fountain at the entrance to purify themselves, visited with friends and went to the front of the temple to invoke the spirits by clapping their hands three times. Most people tossed coins and paper money into a canvas at the foot of the altar. Then they moved to a stand to the side of the temple to buy decorated arrows and paper strips with fortunes written on them. The paper strips were tied to bushes and trees on the temple grounds.

Most of the women wore traditional kimono. Men were dressed in hakama or business suits. The kimono added brilliant color to the bare midwinter landscape and were a strong contrast to the grey, natural weathered wood of the temple. In only two weeks, the girls who turned twenty-one would be dressed in the most colorful kimono they would ever own. Many of them were out on New Year’s to show off their new kimono ahead of time. I enjoyed that aspect of New Year very much. During most of the rest of the year, we did not see kimono as women wore them only for extra special occasions or for performances.

I had been back at the house only a little while that morning when Dr. Mori and his entire family arrived. Mrs. Mori and the three girls were dressed in kimono, Dr. Mori in hakama. Dr. Mori carried a bushel carton full of mikan oranges which he left in the genkan.

We served tea and some of Janelle’s homemade cookies and visited for a few minutes before they left to continue calling on friends and relatives. Because Dr. Mori was a bright, industrious young doctor who was becoming influential among the community and was already recognized for his skill in cardiovascular research and surgical skill, we were honored that he was the first visitor of the year and looked forward to good fortune.

Several people dropped by. Mr. Nakano and his wife knocked at the door, but did not come in. They handed Janelle and Philip envelopes with woven rice ribbon decorations on them.

“This good tradition for children, otoshidama,” he explained haltingly. Inside each envelope were one thousand yen notes.

Janelle and Philip both went out to visit or to play with their friends and later in the day returned with several more otoshidama envelopes with money in them. They both thought we should adopt this particular New Year custom.

Happy New Year

Kenneth Fenter

No comments:

Post a Comment